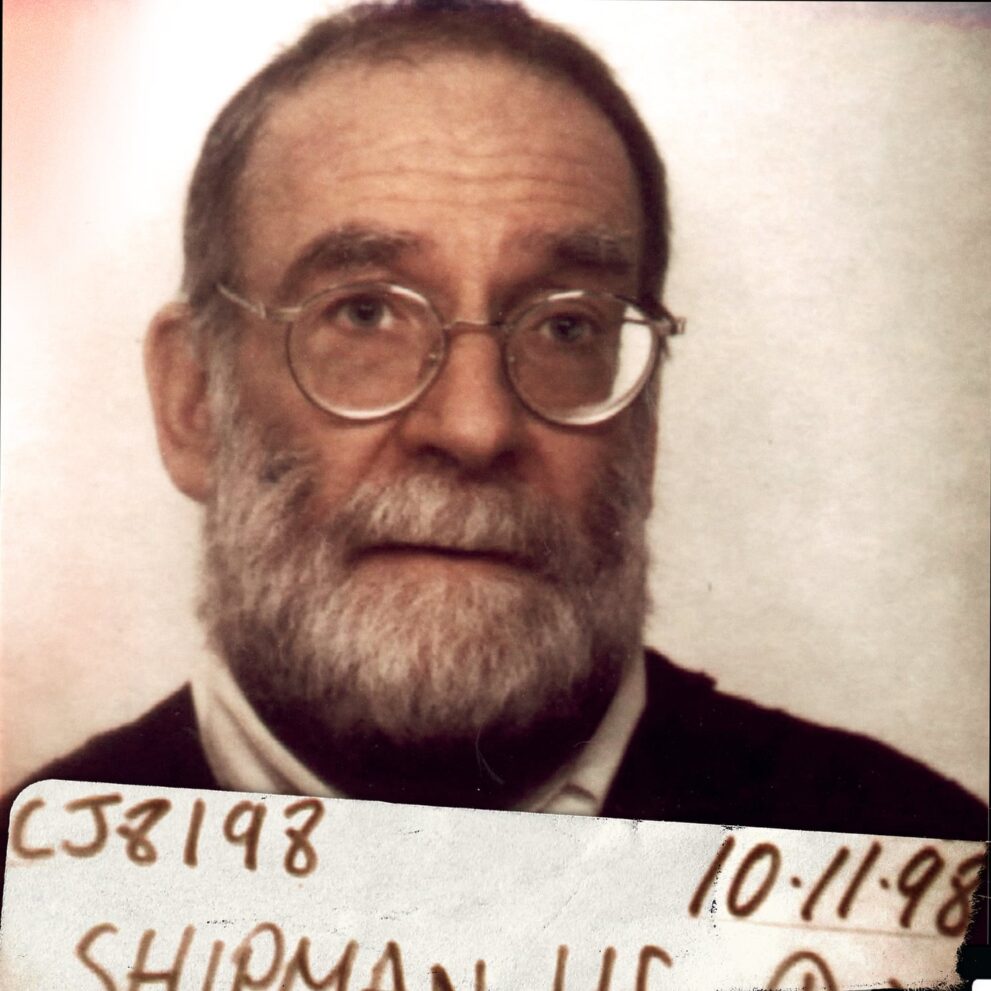

Harold Frederick Shipman was born in 1946 in Nottingham into a working-class family. The youngster, who went by the name Fred, had a peculiar upbringing. Although he had a brother and a sister, it was obvious that he was his mother’s favorite. She believed Fred was destined for greatness and instilled in him a sense of superiority over his peers, despite the fact that he was not very bright and had to work extra hard to attain academic achievement. He established few friendships with other children during his school years, a condition compounded when his mother was diagnosed with lung cancer. Shipman assumed the position of caregiver for his mother, spending time with her after school while waiting for visits from the family doctor, who would inject her with morphine to alleviate her suffering. It is probable that the stress of this event during his early years pushed him into mental illness, compelling him to re-enact the position of caregiver and physician in the macabre manner in which he subsequently did.

Shipman’s mother died of cancer at the age of seventeen, following a lengthy and agonising illness. Despite having to retake his entrance examinations, he enrolled in medical school. Despite his athletic ability, he made little attempts to establish friends. However, it was during this period that he met and married his future wife, Primrose; the couple would have four children before Shipman began his profession as a general practitioner. While he appeared to be kind and nice to many, colleagues complained about his condescending attitude and roughness. He then began experiencing blackouts, which he chalked up to epilepsy. However, troubling evidence surfaced that he was in reality abusing pethidine under the guise of prescribing it to patients. He was expelled from practice, but within two years, he was back working as a doctor, although in a different place.

Shipman quickly acquired the respect of his colleagues and patients in his new position due to his diligence. He is thought to have murdered at least 236 victims during his twenty-four-year tenure at Hyde. For many years, his reputation as a community pillar, not to mention his affable bedside manner, concealed the reality that the mortality toll among Shipman’s patients was startlingly high. Several people have expressed worry over the years regarding the deaths of Shipman’s patients, including families of the deceased and local undertakers. His victims were invariably found sitting in a chair, fully dressed, rather than in bed, and typically had no prior history of fatal disease. The police were notified and conducted an examination of the doctor’s records, but discovered nothing. Shipman eventually admitted to falsifying medical records, but his calm demeanor shielded him from further examination at the time. Shipman then committed a grave error. Kathleen Grundy, an 81-year-old former mayor with a reputation for community engagement, died unexpectedly at home in 1998. Shipman was summoned and proclaimed her dead; he also stated that there was no need for a post-mortem because he had paid her a visit just before her death. After Mrs. Grundy’s burial, her daughter Angela Woodruff got a poorly written copy of her will, which left a sizable inheritance to Shipman. Mrs. Woodruff, a solicitor herself, recognised the forgery instantly. Mrs. Grundy’s body was exhumed following her contact with the police. They discovered a fatal quantity of morphine had been supplied to her. Surprisingly, Shipman made no attempt to conceal his involvement in Mrs. Grundy’s death, whether by meticulously forging the will or by using a less clearly detectable poison. Nobody knows for certain whether this was due to sheer hubris and ignorance, or an underlying wish to be known. However, as the exact cause of Mrs. Grundy’s death was established, further graves were unearthed and additional murders were discovered.

Shipman shown no remorse during his trial for the fifteen homicides for which he was charged. Although further charges were pending, they were more than sufficient to warrant a life sentence. He was dismissive of the police and the court, and he maintained his innocence to the bitter end. He was imprisoned after being convicted of the killings. He killed himself in his jail cell four years later, apparently without warning. Harold Shipman’s case remains puzzling to this day: there was no sexual reason for his murders, and there was no profit motive until the very end. His assassinations did not follow a typical serial killer’s routine. In the majority of cases, it appears as though his victims died peacefully. As some critics have noted, he may have taken pleasure in the notion of having control over life and death and developed an addiction to this sense of power over time. What is obvious is that by ultimately killing himself, Harold Shipman maintained ultimate control: that no one would ever truly comprehend why he did what he did.