Throughout history, the predominant method for instructing and acquiring knowledge of anatomy has been, and continues to be, the dissection of deceased human bodies. Traditionally, surgeons have acquired their profession by initially witnessing surgeries in person and subsequently honing specific abilities, such as suturing, through animal experimentation. Conventional protocol in medical schools dictates maintaining a distance of a few meters from the operating table to observe the skilled practitioners without causing any disruption to surgeons, assistants, or hindering access to instruments. Several universities and institutes offer dedicated observation platforms, however, the need to physically be present in the operating room has become obsolete with the introduction of video cameras. However, what were the methods employed in the past to educate individuals in the field of medicine?

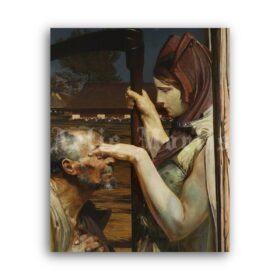

During the Renaissance, numerous institutions were equipped with dedicated operating rooms that featured galleries, allowing students to observe surgical procedures. The venues were referred to as anatomical theaters. An operating table, where surgeons performed their job, was situated in the middle of the theater. Several tiers of seats encircled the table, resembling those found in a Roman amphitheater. From these vantage points, spectators had a clear and unobstructed view of the events.

Undoubtedly, a few of the doctors appeared to get pleasure from the awe-inspiring nature of their profession. Scottish surgeon Robert Liston (1794 – 1847) frequently held a bloodied knife between his teeth in order to ostensibly “liberate his hands,” despite having helpers available. Ironically, Liston was among the pioneers who consistently practiced handwashing prior to surgery and promoted sanitation and hygiene in the operating theater.

Anatomical theaters were initially established in Italy during the 15th century in response to the growing need for medical education and research. The anatomical theater was initially described by Alexander Benedetti in 1493.

“To facilitate the arrangement of a temporary theater, it is advisable to select a spacious and well-ventilated room. The room should be large enough to accommodate a significant number of spectators without causing any disruption to the individuals performing dissections.” These should be experienced people who have performed many autopsies. The allocation of seats should be based on hierarchy. An allocation should be made for a prefect who will supervise all activities and assign seats. It is necessary to have security personnel to control the impulsive public at the entry. Two reliable individuals should be selected to handle the required financial transactions using the gathered funds.

During that time period, autopsies were infrequent. The church imposed severe regulations on the practice, permitting only a limited number of autopsies annually. Frederick II (1194 – 1250), the Holy Roman Emperor, mandated that anybody pursuing a career in medicine or surgery must participate in a post-mortem examination of a human body, to be conducted at least once every five years. Furthermore, due to a scarcity of corpses, numerous anatomists were compelled to employ illicit methods like as exhuming graves, unlawfully procuring bodies, and, according to some accounts, even engaging in homicide.

Historically, anatomical theaters were impermanent edifices, frequently constructed away from the main campus. In 1594, the University of Padua in northern Italy constructed the inaugural permanent anatomical theater. The establishment of anatomy in the 16th century was a significant milestone in medical science, as it established the foundation of medical research.

The Anatomical Theater in Padua comprised of six rows and accommodated approximately 250 spectators. The initial row was designated for anatomy professors, city and university rectors, counselors, members of the medical college, and Venetian nobility. The second and third rows were allocated exclusively for pupils. The fourth, fifth, and sixth seats were allocated for additional spectators. Due to the absence of chairs, the individuals in attendance were compelled to remain standing while observing the autopsy of human cadavers, primarily consisting of condemned criminals or deceased hospital patients.

The complete postmortem examination occasionally required a duration of up to fourteen days. During the intermissions, musicians were invited to provide entertainment for the spectators, while fragrant candles were burned to mask the unpleasant odor. The autopsies were primarily conducted during the winter months, when the rate of decomposition was reduced. Would you have been present at such a performance?

The theater was utilized until 1872, at which point the medical school relocated to the former St. Matthias Convent. The theater is regarded as a source of institutional pride and remains intact to this day.

In 1597, a mere three years following the establishment of the anatomical theater in Padua, a second permanent theater was built in Leiden, Holland. This endeavor was spearheaded by Pieter Pauw, a professor of anatomy at Leiden University. The Leiden theater included six rows, which were characterized by their greater width and spaciousness compared to the Paduan theater. During the winter season, public autopsies were conducted to educate students, surgeons, and members of the public who were interested, in exchange for a specific price. During the summer, the theater was utilized to exhibit a diverse range of peculiarities, such as human and animal skeletons, Egyptian mummies, Roman antiques, and numerous other extraordinary artifacts sourced from different parts of the world. The theater became a major tourist attraction due to these exhibitions. The closure occurred in 1821 with the relocation of the anatomy department to a newly constructed facility.

In 1636, a significant anatomical theater was constructed in London at the Barber Surgeons’ Hall. The theater resembled the one in Padua in terms of its size and shape, however it had four rows of seats instead of six. The seats were meticulously crafted from timber while the walls were adorned with intricate depictions of the zodiac signs. Specially designed compartments and supports were created to house skeletons and other displays, such as an ostrich skeleton and a sculpture of King Charles I. The public autopsies were elaborate spectacles that spanned three days and culminated with a lavish banquet.

Bologna, Italy housed one of the most exceptional anatomical theaters. The construction of the building, which was located in the Palazzo Archiginnasio, spanned a period of 12 years and was finalized in 1637. The walls were constructed using spruce wood, while the ceiling was made of cedar. Positioned at a height of three meters above the floor, the professor’s chair was located. The structure was topped with a canopy and adorned with a sculpture of a sitting female figure symbolizing Anatomy, accompanied by a little cupid carrying a thigh bone. The theater was revered and admired for a span of three centuries. It was utterly devastated during World War II. The structure was subsequently reconstructed utilizing all the original components recovered from the debris of the edifice.

Anatomical theaters had grown outdated by the early 20th century. Following the introduction of anesthetics, the necessity for performing surgery urgently became obsolete. However, it was the microbial theory that ultimately sealed the fate of the anatomical theater. The recognition that both spectators and doctors could serve as carriers of germs prompted the implementation of stricter regulations, ultimately resulting in the transformation of the traditional anatomical theater into the sterile setting characteristic of modern operating rooms.